TREATISE ON CONTERPOINT AND FUGUE (Parts 11 to 12)

This synthesis on Baroque counterpoint and Bach explains how music gradually moves from modality to the major–minor tonal system and how cadences acquire a structural role; it presents basso continuo as a flexible harmonic foundation capable of supporting textures ranging from melody-and-accompaniment to learned polyphonic writing, defines the fugue primarily as an imitative technique, and shows the rhetorical use of expressive dissonances, suspensions, and appoggiaturas, concluding with Bach’s pedagogical function in collections designed for training the ear and composition.

PART XI – Counterpoint in the Baroque

XI.1 Tonal Consolidation

XI.2 Difference between Modal and Tonal Counterpoint

XI.3 Basso Continuo and Counterpoint

XI.4 Independence of Voices

XI.5 Baroque Imitative Counterpoint

XI.6 Relationship between Counterpoint and the Fugue

XI.7 Instrumental Counterpoint

XI.8 Vocal Counterpoint

XI.9 Expressive Use of Dissonance

XI.10 Sequences and Motivic Development

XI.11 Contrapuntal Texture

XI.12 Structural Function

XI.13 Baroque Canon

PART XII – Counterpoint in Johann Sebastian Bach

XII.1 Historical Synthesis

XII.2 Renaissance Influence

XII.3 Harmonic Integration

XII.4 Advanced Imitative Counterpoint

XII.5 Invertible Counterpoint

XII.6 Use of the Canon

XII.7 Relationship with the Fugue

XII.8 Keyboard Counterpoint

XII.9 Vocal Counterpoint

XII.10 Structural Complexity

XII.11 Perceptual Clarity

XII.12 Pedagogical Function

XII.13 Bachian Canon

PART XI – Counterpoint in the Baroque

XI.1 Tonal Consolidation of Counterpoint

During the Baroque period, counterpoint develops in parallel with the gradual consolidation of the major–minor tonal system.

This process is observable approximately between 1600 and 1750, with documented regional variations.

Counterpoint does not immediately abandon modal thinking.

Rather, it gradually integrates functional relationships such as tonic and dominant.

Thus, Baroque counterpoint articulates harmonic hierarchies without relinquishing linear primacy.

XI.2 Difference between Modal Counterpoint and Tonal Counterpoint

Modal counterpoint is organized around modal finals and traditional intervallic relationships.

By contrast, tonal counterpoint is structured around stable tonal centers.

Cadences acquire an explicit structural function.

Dissonance directs the musical discourse toward functional resolutions.

This distinction reflects a gradual historical transformation, not an abrupt rupture.

XI.3 Basso Continuo and Counterpoint

Basso continuo constitutes a fundamental framework of Baroque counterpoint.

The bass line functions as a structural harmonic support.

However, it does not replace the independent voice-leading of the upper parts.

Counterpoint maintains linear autonomy within figured accompaniment.

This system is widely documented in seventeenth-century treatises and practical sources.

XI.4 Independence of Voices

Vocal independence remains a governing principle of Baroque counterpoint.

Each voice preserves a clearly identifiable melodic profile.

Contrary motion is favored for structural reasons.

Perfect parallels continue to be systematically avoided.

Counterpoint becomes denser without losing perceptual clarity.

XI.5 Baroque Imitative Counterpoint

Imitative counterpoint acquires broad formal significance.

Successive entries of the subject organize entire sections.

Procedures such as stretto, augmentation, and diminution are systematized.

Counterpoint becomes the engine of musical development.

This approach directly prepares the language of the fugue.

XI.6 Relationship between Counterpoint and the Fugue

The fugue represents a highly systematized application of imitative counterpoint.

It is not an independent form detached from contrapuntal technique.

Counterpoint structures exposition, development, and conclusion.

Formal coherence depends on imitative treatment.

This relationship is extensively documented in historical analyses.

XI.7 Instrumental Counterpoint

Instrumental counterpoint allows for greater rhythmic and technical complexity.

The absence of text liberates the melodic line.

Sequences and modulations are expanded.

Instrumental counterpoint reaches high levels of density.

Organ, harpsichord, and violin play central roles.

XI.8 Vocal Counterpoint

Vocal counterpoint preserves principles inherited from the Renaissance.

Textual intelligibility remains a priority.

Dissonances are subordinated to rhetorical discourse.

Nevertheless, Baroque counterpoint intensifies expressivity.

This balance defines much of the sacred repertoire.

XI.9 Expressive Use of Dissonance

Dissonance fulfills an expressive function within Baroque counterpoint.

Suspensions and retardations intensify affective tension.

Preparation and resolution remain normative.

Counterpoint dramatizes the rule without abolishing it.

This practice is documented in theoretical and musical sources.

XI.10 Sequences and Motivic Development

Sequences are integrated as a structural resource of counterpoint.

They allow controlled formal expansion.

Motives are transformed through systematic transposition.

Counterpoint ensures discursive continuity.

This procedure is characteristic of the Baroque style.

XI.11 Contrapuntal Texture

Baroque contrapuntal texture combines density and transparency.

Voices retain perceptible independence.

Clear functional hierarchies are established.

Counterpoint organizes texture as a dynamic system.

There is no static homogeneity.

XI.12 Structural Function

Counterpoint fulfills an architectural function.

It does not act as mere technical ornamentation.

It determines formal proportions and tensions.

Large-scale form depends on contrapuntal design.

This principle is verified in extended works.

XI.13 Baroque Canon

The canon is integrated into counterpoint as a strict procedure.

It is employed for pedagogical and compositional purposes.

Canonic entries coexist with controlled harmonic freedom.

Canonic counterpoint demonstrates a high level of technical mastery.

This approach anticipates later developments.

PART XII – Counterpoint in Johann Sebastian Bach

XII.1 Historical Synthesis of Counterpoint

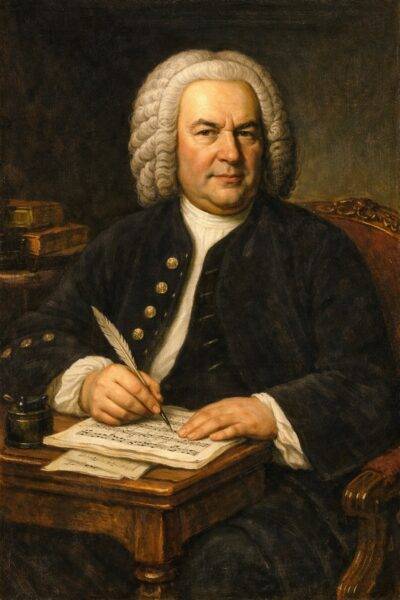

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) represents a historical synthesis of Western counterpoint.

He integrates medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque traditions.

In Bach, counterpoint reaches an exceptional degree of technical and expressive coherence.

This assessment reflects historiographical consensus.

It does not imply the absence of historical precedents.

XII.2 Renaissance Influence

Bach assimilates Renaissance vocal counterpoint.

The influence of Palestrina appears in the treatment of dissonance.

Melodic linearity is a priority.

Counterpoint preserves inherited structural clarity.

This influence is documented by stylistic analysis.

XII.3 Harmonic Integration

Bachian counterpoint fully integrates tonal harmony.

Each line generates functional harmonic implications.

There is no opposition between verticality and horizontality.

Counterpoint governs harmonic progression.

This balance defines his compositional language.

XII.4 Advanced Imitative Counterpoint

Imitation reaches a highly elaborated level in Bach.

Counterpoint employs inversion, augmentation, and simultaneous combination.

Subjects retain recognizable identity.

Technical control is exceptionally rigorous.

This level is widely acknowledged in specialized literature.

XII.5 Invertible Counterpoint

Invertible counterpoint occupies a central position in Bach’s work.

Voices exchange positions without producing harmonic errors.

This procedure requires rigorous structural planning.

Counterpoint becomes reversible.

Examples abound in fugues and canons.

XII.6 Use of the Canon

The canon functions as a laboratory of Bachian counterpoint.

Bach explores canons at the unison, octave, and other intervals.

He employs perpetual and enigmatic canons.

Counterpoint reaches a high degree of abstraction.

These works possess both artistic and pedagogical value.

XII.7 Relationship with the Fugue

The fugue constitutes a central application of counterpoint in Bach.

Each fugue explores distinct technical solutions.

Counterpoint organizes form and development.

The fugue depends structurally on contrapuntal technique.

This relationship is firmly documented.

XII.8 Keyboard Counterpoint

The keyboard allows multiple independent voices to be condensed.

Counterpoint becomes self-sufficient.

The hands realize differentiated lines.

Pedal reinforces structure.

The Well-Tempered Clavier clearly demonstrates this.

XII.9 Vocal Counterpoint

Bach’s vocal counterpoint integrates technique and textual rhetoric.

Each line serves the meaning of the text.

Imitation reinforces semantic content.

Counterpoint functions as an expressive medium.

This principle is evident in cantatas and passions.

XII.10 Structural Complexity

The complexity of counterpoint in Bach is always functional.

It is neither gratuitous nor ornamental.

Each difficulty responds to a formal necessity.

Counterpoint organizes the musical whole.

This trait historically distinguishes his work.

XII.11 Perceptual Clarity

Despite density, Bach’s counterpoint maintains clarity.

Voices remain audibly distinguishable.

Intelligibility is a guiding principle.

Counterpoint does not sacrifice comprehension.

This balance is widely recognized.

XII.12 Pedagogical Function

Bach conceives counterpoint as a formative discipline.

His works function as progressive didactic material.

Learning integrates technique and listening.

Counterpoint becomes a method.

This function is historically documented.

XII.13 Bachian Canon

The Bachian canon represents a culmination of strict counterpoint.

It integrates technical rigor and musical expressivity.

Art and technique are not separated.

Counterpoint achieves exemplary synthesis.

This practice remains a normative reference.

COMPARATIVE TABLE: COUNTERPOINT IN THE BAROQUE AND COUNTERPOINT IN J. S. BACH

| Topic | Baroque (c. 1600–1750) | Bach (1685–1750) | In One Sentence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Musical system | Coexistence of modal and tonal traits; gradual movement toward the major–minor system, uneven by region and genre. | Very stable major–minor tonality, with deliberate use of historical idioms (stile antico) when appropriate. | Baroque = transition and mixture; Bach = mature, conscious synthesis. |

| Cadences and direction | Cadences gain structural weight, though early Baroque may show less “functional” directionality depending on context. | Cadences and tonal planning are integrated into imitative design and formal architecture. | In Bach, cadence is often “structure,” not merely local closure. |

| Basso continuo | Central framework: bass plus figures guide realization; supports textures from melody–accompaniment to highly contrapuntal writing. | The bass may function both as support and as a structural or thematic voice within the texture. | Continuo = flexible foundation; in Bach it is integrated into the global design. |

| Independence of voices | A strong ideal in learned contrapuntal writing; avoidance of perfect parallels is normative there, but not all Baroque genres pursue equal independence. | High density with voices clearly distinguished by register, rhythm, and motive; clarity even in complexity. | Baroque: genre-dependent; Bach: consistent clarity in contrapuntal writing. |

| Imitation | Imitation organizes sections; stretto, augmentation, and diminution are frequent in imitative repertories (not in all Baroque music). | Advanced combinatorial technique: inversion, augmentation, and superimposition under extreme control. | Bach brings imitation to the highest level of combination. |

| Fugue | Primarily a compositional procedure with conventions; the term may also designate a work or section. | A central “laboratory”: each fugue explores distinct technical and expressive solutions. | Fugue = technique (and sometimes a piece); Bach turns it into a total art. |

| Instrumental writing | Greater rhythmic and technical freedom; sequences and modulations expand, especially in instrumental genres. | The keyboard condenses voices; maximum precision of layers, entries, and articulation. | Baroque instrumental music opens the field; Bach masters and organizes it. |

| Vocal writing | Text and rhetoric prioritize intelligibility; complexity is possible, but text guides the music. | Technique plus rhetoric: counterpoint reinforces textual meaning (cantatas, passions). | In Bach, counterpoint “explains” the text musically. |

| Dissonance | Normative suspensions and retardations, plus accented dissonances (appoggiaturas) with affective weight; rules exist but vary by style. | Expressive dissonance integrated into tonal direction and form; tension serves structural purpose. | Dissonance = regulated emotion; in Bach = emotion plus architecture. |

| Sequences | Typical resource for expansion and connection; function varies by genre (bridge, extension, emphasis). | Sequential episodes often modulate and prepare imitative reentries or climaxes. | Sequence = continuity; in Bach = continuity with formal goal. |

| Texture | Alternation between dense and transparent textures; hierarchies depend on genre (continuo may yield more homophonic or polyphonic textures). | High density with designed hierarchy; motivic design clarifies “who carries the idea.” | Baroque: variable texture; Bach: intelligible density. |

| Structural function | In contrapuntal genres, counterpoint may be architectural; in others, more local or ornamental. | Complexity is almost always functional: every device contributes to direction, climax, or closure. | In Bach, nothing “difficult” is gratuitous. |

| Canon | Strict procedure used for pedagogical and artistic purposes; reference point for later tradition. | Culmination: varied canons (including enigmatic and perpetual) with full musicality. | Canon = proof of mastery; Bach elevates it to a model. |

| Didactics | Broad teaching tradition (counterpoint, continuo, models). | Collections with explicit pedagogical intent (e.g., clarity in 2–3 voices, composition). | Bach teaches ear, technique, and composition simultaneously. |